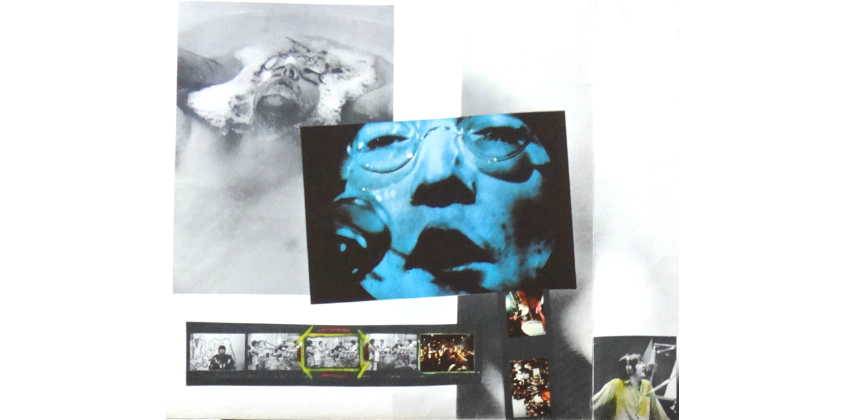

Revolution 9, a soundscape produced by John Lennon and appearing on The Beatles White Album, is brilliant.

Lennon’s idea was to give an audio representation of what revolution sounded like to him and, in setting a mood of unease, unpleasantness, and paranoia, he achieves just that. Anyone who has listened to this piece with headphones in a dark room knows that it is creepy and will have you looking over your shoulders.

Backwards loops, short sound clips, and stereo panning are just some of the tools Lennon, and presumably Yoko Ono, used to really drive home the uneasy feeling. Upon closer inspection, however, this piece is constructed in a very musical, almost, symphonic way. There are recurring themes and motifs (obviously the “number 9) ranging from short pieces of dialog and chanting to piano underscore and symphonic loops. These little themes appear throughout the entire piece and ground it in some form of familiarity.

Also, the piece starts off simple, with a piano motif that sneaks in throughout the track, and the panned “number 9” vocals. The piece builds on that, often introducing several motifs simultaneously, until there is a cacophony of noise. Several times the tension is pushed to a near breaking point and then relieved only to be pushed all the way back again. How is this any different than the chordal and rhythmic dissonance that classical composers have been using for years?

Instead of using conventional instruments and musical ideas, Lennon is using sounds from every source he can get his hands on to create the same textures, emotions and tensions that a composer would create in a symphonic piece. While “Revolution 9” hardly ranks among the great compositions of the 20th century, it is not without artistic merit and deserves a closer inspection by listeners.

Listen for the recurring themes throughout the piece. Within the first few seconds of the collage you are introduced to several short snippets and, around the 50 second mark, many of those snippets are superimposed on top of one another to create a contrapuntal recapitulation of what you’ve already heard. The build is relieved around the 1:00 marker when it’s all stripped down to the backwards flutes (or whatever it is) which fade out to reveal the quiet piano passage that opened the song.

Along with all of these things there are bits of dialog, sounding mostly to be Lennon and Harrison, that could be considered variations on a theme or, possibly, a development section. Again, as was done in the first minute, the noise builds and grows in chaos only to be stripped back at the 1:45 mark to ladies laughing, the “number 9”, a baby cooing and some new short snippets that we have not heard before but that are, presumably, from the same source as other pieces we have heard. And what should enter around the 2:05 mark? The piano music that opened the piece.

Without analyzing the entirety of this piece, it goes further into the realm of classical composition than most rock and roll pieces and beyond the sheer insanity of the piece lies something that is musically satisfying, despite not being musically pretty. Take a listen on the video below and really focus on picking out the little odds and ends that I’ve mentioned.

Revolution 9 is not likely to be the first dance at your wedding but it is not without artistic merit and maybe gets an undeserved bum deal.

Now that you’ve heard Revolution 9, share your thoughts. Are you able to get past the strangeness of it all to appreciate it as an artistic aural landscape or is it just too weird to be taken seriously?

In case you’re still on the fence about its “classical sensibilities” let me share with you this live cover that a reader shared with me. This is a very loyal transcription, complete with stereo panning effects, vocals, and, with some creative technique from the instrumentalists, the effect of backwards tape loops. This may be the greatest Beatles cover I’ve ever heard.